The experimental facility consists of a Ma = 5 in-draft wind tunnel, an integrated laser system and a jet injection module.

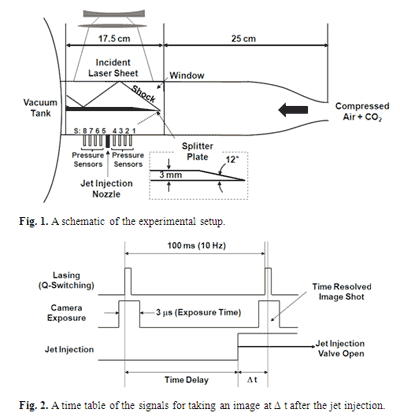

A schematic of the Ma = 5 wind tunnel is shown in Fig. 1. Air at high pressure (P0 = 350 kPa and T0 = 300 K) containing CO2 (approximately 25% by volume) expands through a converging/diverging nozzle (25:1 area ratio) to establish a relatively uniform Ma = 5 flow in a rectangular test section (4 cm × 4 cm cross-sectional area). The exit of the tunnel is connected to a vacuum tank that accommodates the incoming mass flow for approximately 5 seconds of run time. During this run time, the vacuum tank pressure is maintained at values lower than the static pressure in the test section. A honeycomb of 2.5 cm in length and 3 mm hexagonal cells is placed upstream of the converging nozzle to suppress flow swirling, mostly generated at various junctions in the gas stream inlet piping. The static pressure and temperature of the flow in the test section is approximately 1 kPa and 50 K, respectively.

A detailed characterization of the variation in Mach number of the flow across the test section is carried out by measuring the shock angle from a sharp leading wedge of 12° angle using Schlieren photography. The measured Mach number midway across the tunnel is approximately Ma = 4.9, with a 5 % variation wall to wall (boundary layers were not resolved). Windows on both sides of the test section and transparent upper/lower walls allow optical access. A 3 mm thick splitter plate(aluminum plate), having a sharp leading wedge and a transparent slotof an embedded acrylic plate divides the test section into two parts of equal cross sectional area. The sharp leading wedge of an asymmetric design (12° angled wedge in the top half of channel), as shown in Fig. 1, is used to generate a relatively shock-free flow in the lower half while it causes a shock train in the upper half. Static pressure traces on the bottom wall of the tunnel are recorded using eight fast response (100 kHz) pressure sensors (S1 – S8: PCB Piezotronics, Model 113A26). The sensors and the jet injection nozzle, placed between S4 and S5, are separated by 15 mm along the centerline of the bottom wall parallel to the free stream flow direction: S1 and S8 are located 60 mm upstream and downstream from the nozzle, respectively. The distance between the tip of the splitter plate (270 mm downstream from the converging/diverging nozzle throat) and the nozzle is 75 mm.

The experimental components for Rayleigh scattering include a Nd:YAG laser (New Wave, Gemini PIV) capable of generating approximately 100 mJ/pulse (532 nm wavelength) energy with 10 Hz pulse repetition, an unintensified CCD camera (La Vision, Imager Intense) and a computer (not shown) to facilitate data acquisition. The laser beam is transformed into a thin sheet of 0.5 mm thickness to illuminate the test section using a combination of two concave cylindrical lenses and a convex spherical lens. Scattered light is captured by the camera along a direction normal to the laser sheet. Laser firing is synchronized with the CCD camera exposure (3 microns shutter), as illustrated in Fig. 2. One of the laser pulses is selected to trigger the jet injection module while the tunnel is operating, but delayed as desired by a pulse delay generator (SRS, DG 535) to take time resolved images at different phases (Dt following the injection of the jet) in the flow evolution induced by the jet injection. The jet injection is controlled by a solenoid valve (ASCO, Red Hat II) driven by a controller (Optimal Engineering System Inc.) receiving the trigger signal from the delay generator. A sonic jet (air, in these studies presented here) is injected into the test section through a 3 mm diameter hole in the bottom wall resulting in a flow disturbance and an overall increase in flow pressure and temperature. Relevant to the jet interaction and mixing with the supersonic free stream is the square root ratio of the jet momentum flux to that of the free stream (R). For our results described here, R is approximately 4.5.